The Daily Crackers menu (Olympia), courtesy The Seattle Public Library

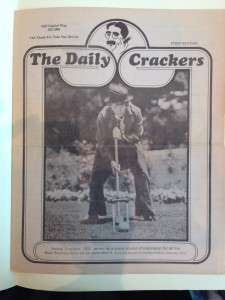

Historic restaurant menus are a road leading to the past. What could one order, say, at Drake’s Restaurant in Seattle on March 11, 1910? Seattle Public Library’s historic menu collection lets us peak over the long-ago waitress’s starched shoulder: Baked ox heart and dressing? That will be 15-cents.

Drake’s Restaurant menu (Seattle) for March 11, 1910, Courtesy The Seattle Public Library

The way we eat has changed in the past century. I’m guessing that few Seattle restaurant patrons now are looking for calf’s brains with scrambled eggs (20-cents), or would count compote of peaches with rice (15-cents) as a main dish. I’ll take the latter.

Our 1910 waitress would have belonged to the Waitresses’ Union, as nearly all of Seattle’s waitresses did. Union rules limited her work hours to ten (before the union organized, 12- to 15-hour shifts were standard), although the boss could still demand her presence seven days a week.

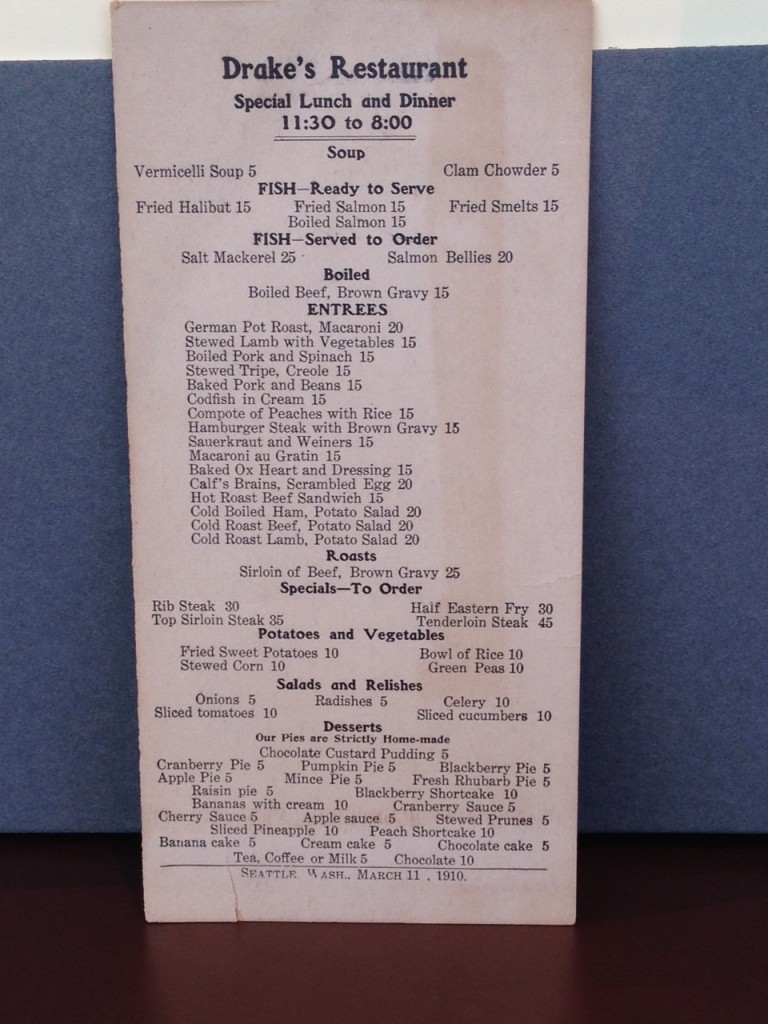

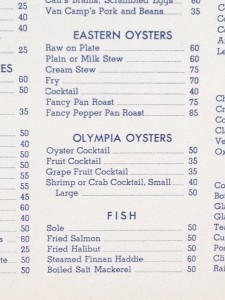

Looking through menus in the Seattle Room is fascinating. How does a time traveler at Holland Hotel and Coffee Shop in 1940 choose which oysters — Eastern or Olympia — to start with, and how (raw, stewed in milk, as oyster cocktail) the delicious morsels should be prepared?

Holland Restaurant menu (Seattle), Courtesy The Seattle Public Library

Oyster choices, Holland Restaurant menu, Courtesy The Seattle Public Library

Seattle Public Library’s menu collection is slowly being digitized (slowly because librarians are adding new menus to the collection steadily — the project is open-ended). Digitized menus can be viewed by anyone: no library card required. Results are sort-able by decade.

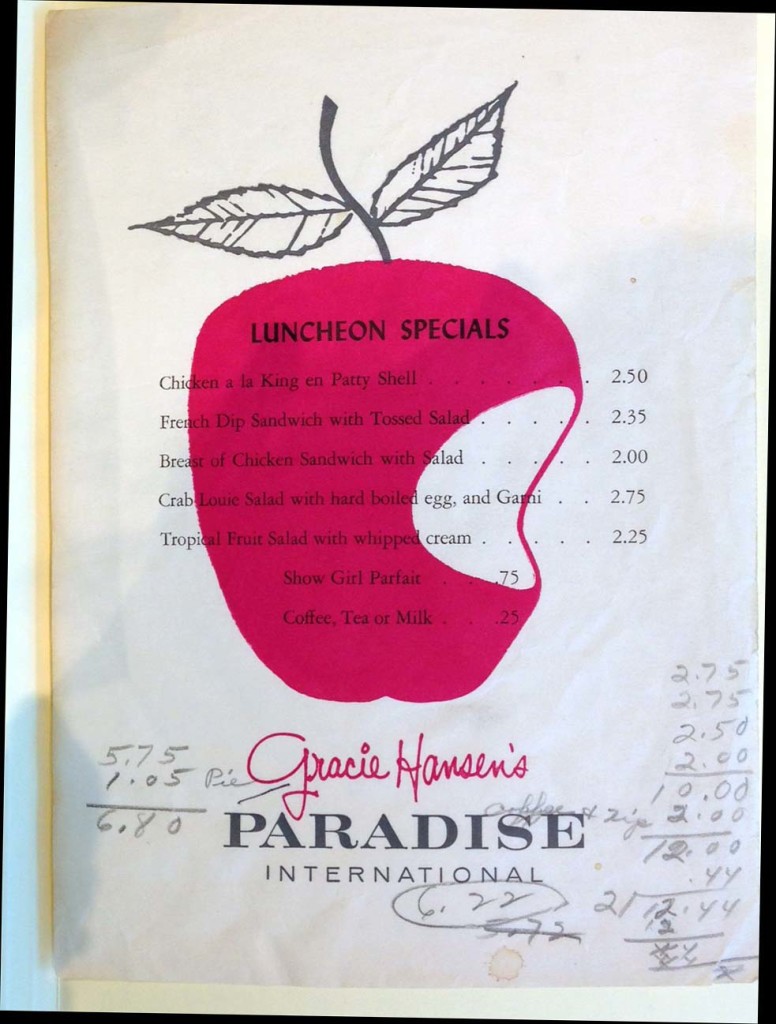

Lunch at Gracie Hansen’s Paradise International, 1962 Seattle World’s Fair, Courtesy The Seattle Public Library

But wait, there’s more! University of Washington Libraries has its own enormous menu collection, also digitized. Who uses these menus? Fiction writers looking for period details, food historians and foodies in general, social historians, graphic designers interested in font choices and layout, and armchair time travelers (of course).

My ironclad rule for archival research is Never Enter An Archive Hungry. When using historic menu collections, this goes double.

June 5, 2015