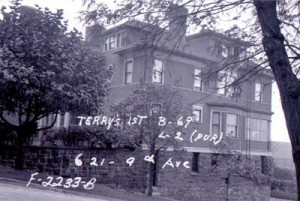

621 9th Avenue, Seattle, Courtesy King County Tax Assessor

The continued existence of the house at 621 9th Avenue is surprising, considering its First Hill location. Tall buildings loom near the capacious dwelling, which is set back from 9th Avenue on the steep corner of Cherry Street. The house dates from about 1900, and surely holds many stories. I’ve never been inside, but I imagine that the view of Elliott Bay from the third floor is breathtaking.

This house was built by Thomas and Virginia Prosch, who lost their lives one hundred years ago this coming Monday — March 30, 1915. Thomas and his father Charles were pioneer newspaper publishers who arrived in the future Washington Territory in 1858. Virginia was the daughter of Morton and Julia Ann McCarver, who founded Tacoma. Thomas and Virginia, artist Harriet Foster Beecher, and philanthropist Margaret Lenora Denny (who as a little girl had been one of the Denny Party pioneers) drowned in the Duwamish River when the car in which they were passengers dodged children playing in the road and veered off the Riverton Draw Bridge.

Prosch House, 1938

Courtesy Puget Sound Regional Archives

Seattle Assay Office/German Club, 1938

Courtesy Puget Sound Regional Archives

Tragedy hounded the Prosch family, both before and after Thomas and Virginia’s deaths. The first of Thomas and Virginia’s five children, Julia, died in infancy. The Prosches’ most insistent tragic arc was their affliction with the fatal White Plague, tuberculosis. Of five Prosch children to reach adulthood, three succumbed to the disease: Genevieve in 1904 at age 19, Beatrice in 1916 at age 30, and finally Edith. Only two of Thomas and Virginia’s children married. None had children.

Edith Prosch, 1901

Courtesy UW Tyee

Edith Prosch’s story is haunting. Summoned from Beatrice’s sickbed to the front door of 621 9th Avenue by the loud knocking of a Seattle Post-Intelligencer reporter hoping for a statement, Edith learned the news of her parents’ deaths. This shock will kill my sister, Edith said, but it was nearly a year after their parents’ funeral that tuberculosis finally finished Beatrice off.

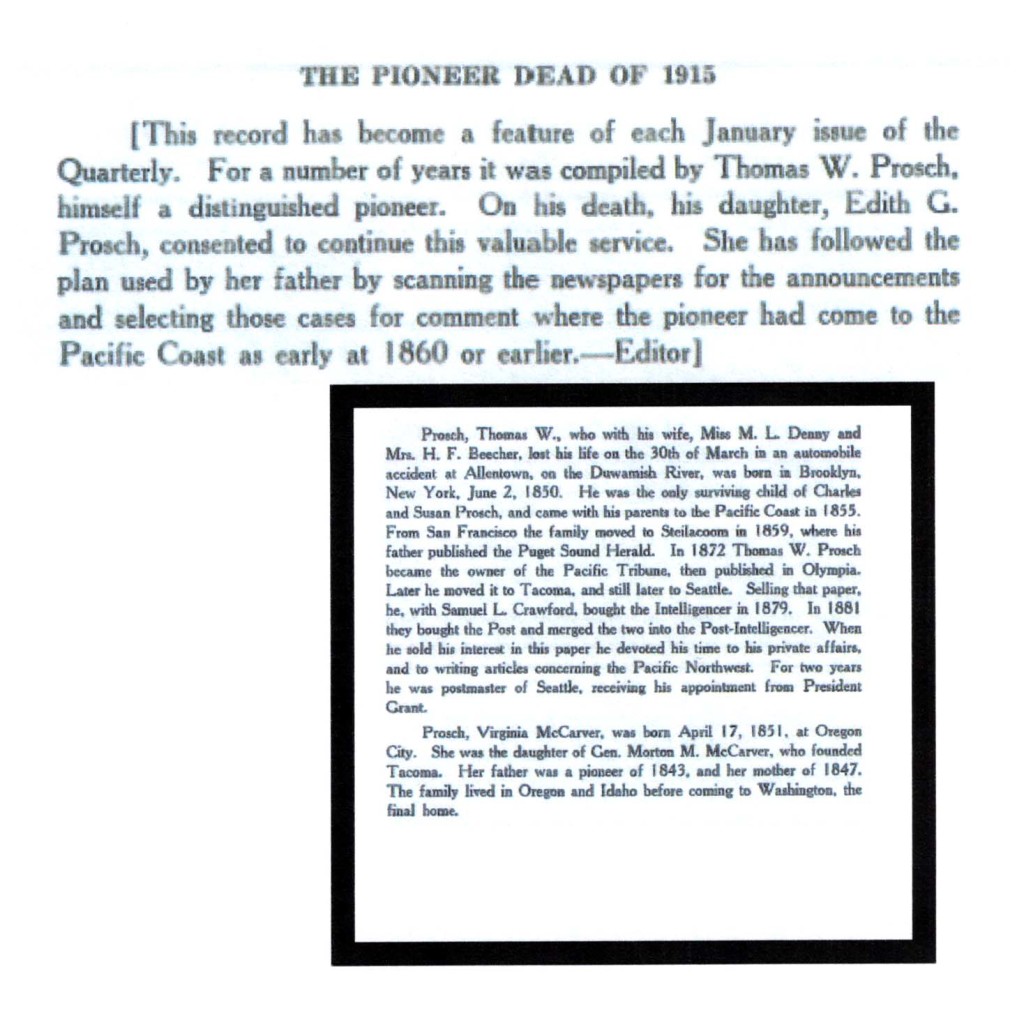

During the months Beatrice was dying, Edith accepted family friend and University of Washington history professor Edmond Meany’s request that she take over the column her late father had written for the Washington Historical Quarterly, “The Pioneer Dead,” a list of brief obituaries of Washington pioneers who’d recently died. Edith’s first column included obituaries for her mother and father. What on earth was Meany thinking, I wonder?

“The Pioneer Dead,” Washington Historical Quarterly, January 1916

Edith had been a vivacious young woman, vice president of the University of Washington’s class of 1901. The family entertained often in their home. Edith volunteered in the community, delivering food to the poor for the Fruit and Flower Mission. She poured tea at Anti-Tuberculosis League fundraisers and (like her mother) was active in the DAR. After her parents’ death, it fell to Edith to liquidate her father’s real estate holdings, consisting mainly of unimproved land on the south slope of Queen Anne hill — there was no money with which to develop the property. Lot by lot, she arduously transferred the land back to the city of Seattle. Edith and her siblings left 621 soon after, but held the mortgage to the house for decades.

Virginia Prosch’s grave, Lake View Cemetery, Seattle

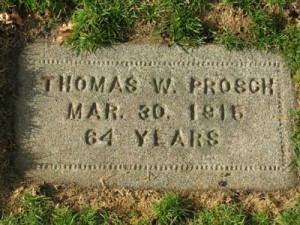

Thomas Prosch’s grave, Lake View Cemetery, Seattle

After Beatrice died, Edith too was diagnosed with tuberculosis. For the next twenty years she split her time between sanatoriums in California and the Seattle home of her youngest sister, Phoebe Prosch Anderson. In 1937, as her condition worsened, 57 year old Edith swallowed hydrochloric acid, leaving notes for Phoebe and for their brother Arthur.

Kafe Berlin, Seattle

The Prosch House (for more than a century operated as a rooming house) shares the block with an historic site, the Assay Office/German Club at 613 9th Avenue, constructed by Thomas Prosch as Prosch Hall in 1886. This structure is landmarked, which may be why the nearby Prosch house has not — like so many of its former neighbors — fallen. A visit to Kafe Berlin, a recent tenant, provides the opportunity to contemplate the Prosch family and the persistence of certain pockets of Seattle’s built environment — long after those who built them have turned to dust.

March 27, 2015